CNN

—

South Korea has a problem: Thousands of people, many of them middle-aged and isolated, die alone every year, often going unnoticed for days or weeks.

It’s about “godoksa”, or “lonely deaths”, a widespread phenomenon that the government has been trying to combat for years as its population ages rapidly.

According to South Korean law, a ‘lonely death’ is when a person who lives alone, cut off from family or loved ones, dies by suicide or illness, with their body only found after ‘a period of time’. .

The issue has captured national attention over the past decade as the number of lone deaths has risen. Factors driving this trend include the country’s demographic crisis, gaps in social protection, poverty and social isolation – all of which have worsened since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Last year, the country recorded 3,378 such deaths, compared to 2,412 in 2017, according to a report published last Wednesday by the Ministry of Health and Social Care.

The department’s report was the first since the government enacted the Prevention and Management of Lonely Deaths Act in 2021, under which updates are required every five years to help establish “prevention policies lonely deaths”.

Although solitary deaths affect people from various demographic groups, the report showed that middle-aged and older men appear to be particularly at risk.

The number of men dying alone was 5.3 times that of women in 2021, up from four times previously.

People in their 50s and 60s accounted for up to 60% of lone deaths last year, with large numbers in their 40s and 60s as well. People in their 20s and 30s made up 6% to 8%.

The report did not go into possible causes. But the phenomenon has been studied for years as authorities try to understand what drives these lonely deaths and how best to support vulnerable people.

“In preparation for a super-aged society, it is necessary to actively respond to lonely deaths,” South Korea’s legislative research body said in a press release earlier this year, adding that the government’s priority is “to quickly identify cases of social isolation”. ”

South Korea is one of many Asian countries – including Japan and China – facing population decline as people have fewer babies and give birth later in life.

The country’s birth rate has been steadily falling since 2015, with experts blaming various factors such as a demanding work culture, rising cost of living and stagnating wages for deterring people from parenting. At the same time, the workforce is shrinking, raising concerns that there may not be enough workers to support the burgeoning elderly population in areas such as health care and help with residence.

Some of the consequences of this skewed age distribution are becoming apparent, with millions of aging residents struggling to survive on their own.

In 2016, more than 43% of Koreans over the age of 65 lived below the poverty line, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, more than three times the national average of other OECD countries.

The life of middle-aged and elderly Koreans “deteriorates rapidly” if they are excluded from the labor and housing markets and it is “a major cause of death”, wrote Song In-joo, senior researcher at the Seoul Welfare Center. a 2021 study of the lonely dead.

The study analyzed nine cases of solitary deaths and conducted in-depth interviews with their neighbours, landlords and social workers.

One case involved a 64-year-old factory worker who died of alcohol-related liver disease, a year after losing his job due to disability. He had no education, family or even a cell phone. In another case, an 88-year-old woman suffered financial hardship following the death of her son. She died after the seniors’ wellness center she attended, which offered free meals, closed at the start of the pandemic.

“The difficulties expressed before death by people at risk of dying alone were health problems, economic hardship, disconnection and rejection, and difficulty managing daily life,” Song wrote.

Compounding factors included delayed government aid and a “lack of home care” for people with serious or chronic illnesses.

The findings of the 2021 study were echoed in the Department of Health and Welfare’s report, which says many at-risk people found their life satisfaction “decline rapidly in due to job loss and divorce” – especially if they were “unfamiliar with health care and housework”. .” .”

Many people in the 2021 study lived in cramped, dark spaces such as subdivided apartments known as jjokbang, where residents often share common facilities, and basement apartments known as banjiha , which made headlines earlier this year when a family was trapped and drowned during record rainfall in Seoul.

In major cities like Seoul, the notoriously expensive housing market means these apartments are among the most affordable options available. And besides poor living conditions, they also carry the risk of further isolation; These housing structures “have already been criticized as slums…and are also stigmatised”, with many residents living “anonymous” lives, according to the 2021 study.

“It’s concerning because the (housing concentration) of lonely deaths could be another feature of the poverty subculture,” Song wrote.

Growing public concern about lone deaths has prompted various regional and national initiatives over the years.

In 2018, the Seoul metropolitan The government has announced a “neighborhood watch” program, in which community members visit single-person households in vulnerable areas such as basement apartments and subdivided dwellings, according to the Yonhap news agency.

Under this plan, hospitals, landlords and convenience store staff act as “gatekeepers”, notifying community workers when patients or regular customers are not seen for an extended period of time, or when rent and other fees are not paid.

Several cities, including Seoul, Ulsan and Jeonju, have rolled out mobile apps for people living alone that automatically send a message to an emergency contact if the phone is idle for a period of time.

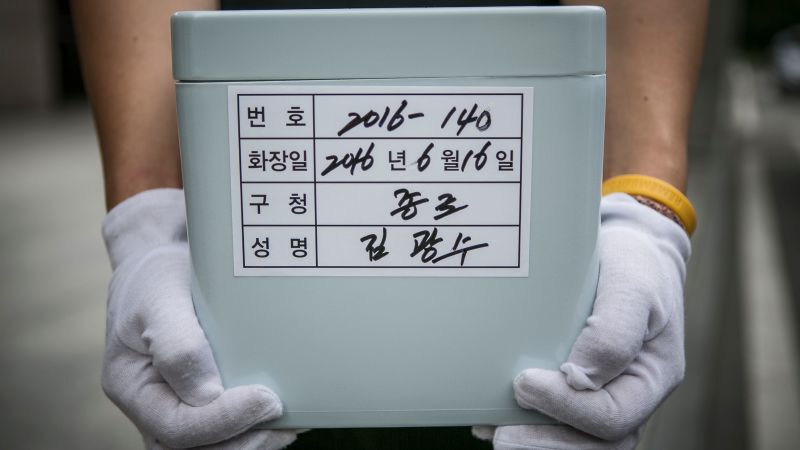

Other organizations such as churches and nonprofits have also stepped up outreach services and community events – as well as handling funeral rites for the deceased who have no one left to claim or mourn them.

The Prevention and Management of Lonely Deaths Act passed last year was the most recent and sweeping measure to date, directing local governments to put policies in place to identify and assist at-risk residents. In addition to establishing the five-year progress report, he also demanded that the government draw up a comprehensive preventive plan, which is still being drawn up.

In another study published in November, Song recommended authorities create more support systems for those trying to get back on their feet, including education, training and counseling programs for middle-aged people. and the elderly.

In a press release accompanying Wednesday’s report, Minister of Health and Welfare Cho Kyu-hong said South Korea was striving to “become like other countries, including the UK and Japan, which have recently launched strategies… (to deal with) the lonely dead.”

“This analysis is significant as a first step for central and local governments to responsibly address this crisis of a new welfare blind spot,” he said.

.

Comments

Post a Comment