CenturyLink customers in Seattle and Portland receive varying levels of service for the same price, with poorer residents and people of color more likely to be overwhelmed by slow speeds, according to a new analysis of the digital divide in US cities.

Seattle had the worst disparities among cities examined in the Pacific Northwest. About half of its low-income areas received slow internet, compared to just 19% of high-income areas. Addresses in neighborhoods with more residents of color also offer slow internet more often: 32.8% of them, against 18.7% of areas with more white residents.

CenturyLink’s offers in Portland were also uneven, as 27% of addresses in low-income areas offered speeds below the federal broadband standard of 25 mbps, compared to 16% of high-income areas. In both Portland and Seattle, neighborhoods ranked as “dangerous” for mortgage lenders on mid-20th-century “redlining” maps — which were used to discriminate against minority communities — were more likely to see the worst internet deals in both cities today.

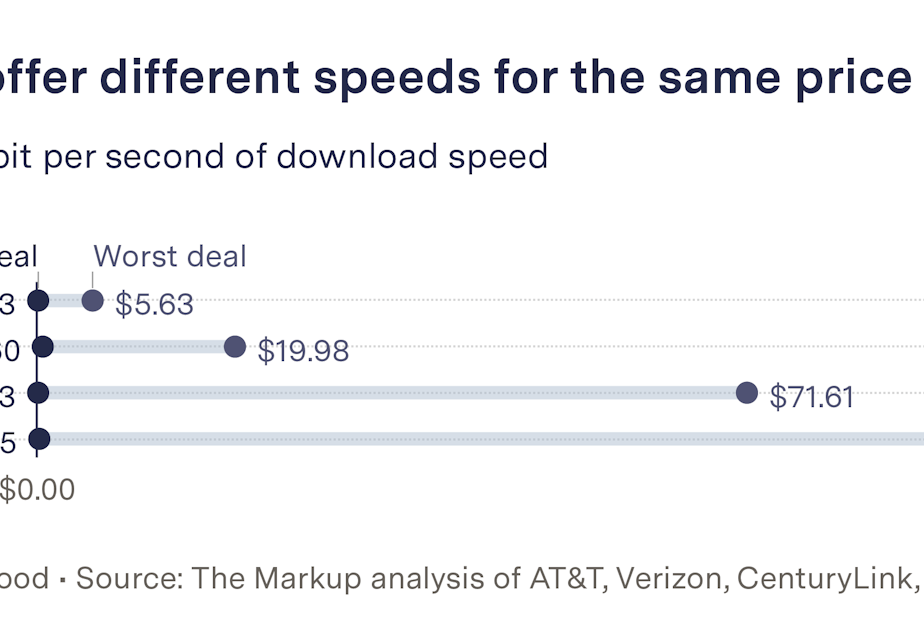

The disparities in the Pacific Northwest’s two largest cities were revealed in a national investigation this fall by The Markup, a nonprofit news agency covering technology’s impacts on society, which showed that four major Internet service providers offer routinely slower speeds for some neighborhoods for the same price. as higher speeds offered to other areas.

Markup analyzed service offerings from CenturyLink, Verizon, AT&T and EarthLink at more than 800,000 addresses in major cities across 38 states. Markup found income-related disparities in Seattle, Portland and 17 other cities. In two-thirds of cities where the media had enough data to compare, the worst deals were offered in the least white neighborhoods.

In addition to Seattle and Portland, the worst deals in 20 other cities line up with old redlining limits. A spokesperson for Lumen, CenturyLink’s parent company, denied discriminatory intent and criticized The Markup’s investigation in a statement.

“The methodology used for the report you read is deeply flawed,” said Mark Molzen in an email. “We do not engage in discriminatory practices such as redlining and we find the allegation offensive. While we cannot comment on behalf of other providers, we can say that we do not offer services based on any consideration of race or ethnicity.”

Comcast, the main Internet service provider for both Seattle and Portland, was not included in the analysis because it does not offer different speeds for the same price, a practice known as “capping.” EarthLink also serves Seattle and Portland, but the analysis showed no evidence of income or race-related disparities.

State and local officials in Oregon and Washington expressed concern but little surprise at the inconsistencies uncovered in the analysis.

“I don’t doubt that disparities exist in Portland,” said Rebecca Gibbons, manager of strategic initiatives at the Portland Office of Community Technology.

While Comcast and one or two other providers also serve cities, the new data reaffirms that low-income residents are stuck with the worst options, Gibbons told InvestigateWest.

“If a consumer has only one choice, they are subject to this level of customer service, these fees, these fees,” she said. “We would like it to be as competitive as possible.”

Oregon Representative Pam Marsh, D-Southern Jackson County, who is on the Oregon Joint Information Technology and Management Committee, said the findings “clearly showed a calculated business decision about who will pay for services.”

“The result is people are left out,” she said.

Level capping is not illegal. While policymakers at all levels agree that broadband is an essential tool for social, economic and educational empowerment, it is not regulated as a public service like electricity. Providers can set their own prices, and state and local authorities cannot force them to build modernized infrastructure in areas that may be less profitable.

While advocates and government officials see an opportunity to provide additional contributions during the allocation of $65 billion in federal funding passed under the Employment and Infrastructure Investment Act of 2021, the money may not bring much relief to underserved urban neighborhoods.

Francella Ochillo, executive director of Next Century Cities, a national nonprofit that advocates for affordable, reliable high-speed internet for all, said The Markup’s analysis of providers sheds light on the plight of underserved residents.

“Companies have very robust communications officers and lobbyists to make sure they convince people that you’re not seeing what you see with your own eyes, but we see it with our own eyes,” said Ochillo. “And we actually have the numbers to prove it.”

But looking at the data is just a first step, she said.

“We created a system where unequal outcomes are guaranteed,” she said. “If we want to have a different outcome, we will not only have to examine but also dismantle some of the practices that got us here.”

neighborhoods left behind

The stories of CenturyLink’s expansion in Portland and Seattle mirror each other.

In 2015, the landline company began looking to compete in the high-speed internet market with cable companies like Comcast, which controlled most of it. CenturyLink pursued cable franchises and licenses and began building its high-speed internet and cable infrastructure, officials said.

Just a few years after expanding into Seattle and Portland, however, CenturyLink’s appetite for expansion as a cable provider has waned, officials said. Gibbons said CenturyLink exited the Portland market in 2020 and the company exited the Seattle cable market in 2021, according to a spokesman for the mayor’s office.

CenturyLink remained an active Internet service provider, but when it stopped expanding as a cable provider, Gibbons said, “our regulatory authority to require them to expand into every borough disappeared.”

As a result, CenturyLink’s deployment in both cities has led to some pretty lopsided scenarios.

In Portland, for example, two blocks north of the Lloyd Center on Broadway Street, CenturyLink offers an office building Internet speeds of up to 15 megabits per second for $50 a month. A mile and a half to the southeast, in the high-income area of Laurelhurst, residents of a house on 35th Avenue could pay $20 less a month for 200 megabits per second — a lower price for speeds 13 times faster.

During its time as an Internet service provider, CenturyLink has clashed with Washington and Oregon attorneys general over complaints about confusing and duplicate billing. In 2020, the lawsuits resulted in a $6 million payout in Washington and a $4 million settlement in Oregon.

A spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Justice said the capping issue does not appear to violate the Oregon Unfair Commercial Practices Act, and no case has been filed against a broadband provider under that law.

State officials and advocates recognized practical factors that contribute to disparities. Building infrastructure is expensive, and companies choose to do so in areas where they think they can cash in on the costs.

But, said Ochillo, “involuntary deletion has a discriminatory impact, whether or not it’s what you intended.

“Communities know when their students can’t go to school online, when their small businesses don’t operate with the same kind of resilience, when they don’t have the same kind of telehealth options as others.”

Big money, few regulations

Internet service providers, or ISPs, also point to their participation in the Affordable Connectivity Program as proof of their commitment to advancing digital equity.

The federal program, launched in 2021 to replace an old broadband program, subsidizes internet for low-income families at $30 a month, or $75 for families on Indian reservations. Many different indicators of economic need can qualify a family for participation in the program, which is administered by the Federal Communications Commission.

Subscriptions are low. Data from mid-2022 show that only 27% of eligible households in Portland and Seattle have enrolled in the program.

Authorities have offered some reasons for this. Marsh, the Oregon state representative, criticized the program for being too reliant on ISP participation, and Gibbons called the registration requirements “too onerous.”

Some aspects of the Infrastructure Investment and Employment Law indicate that the federal government is starting to pay attention to how it can more actively tackle digital inequalities.

For the first time in March, the FCC began soliciting comments on digital discrimination and equity, including “how to implement provisions in the Infrastructure Investment and Employment Act that require the FCC to combat digital discrimination and promote equal access to broadband in across the country, regardless of income level, ethnicity, race, religion or nationality”.

Infrastructure law funding also allows states and localities to evaluate new opportunities before funding is allocated.

In late November, the FCC published its latest broadband map. It is the main resource that the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the executive branch in charge of allocating funds, will use to make decisions. The map is based on self-reported data from ISPs.

“From what we’ve seen on the maps, they’re dramatically exaggerating what their true coverage is,” said Evan Marwell, CEO of EducationSuperHighway, a nonprofit digital heritage advocacy organization.

From now until January, the FCC is accepting challenges from states to tweak the maps. The Washington Department of Commerce and the Oregon Broadband Office issued press releases requesting information from the public regarding the FCC maps, including information on how to submit disputes.

But there’s a caveat for Portland and Seattle: Despite the billions of dollars flowing in, most officials have expressed doubt that urban residents will see much of it.

That’s because Congress required states to first spend infrastructure bill money in areas that are “underserved” or considered to lack broadband access. Neighborhoods where an ISP already offers service, albeit limited, will likely not be touched until rural and remote areas are served first.

It is a sore point for city and state authorities.

“Yes, rural communities where there is absolutely no access – we need to prioritize those,” Gibbons said. “But when you look at the number of communities and you’re using an equity lens, your black people, indigenous people of color, people with disabilities, most of them live in urban communities.”

Ochillo said changes in federal policy are needed for widespread change.

“The ISPs mentioned in the report receive a ton of government subsidies,” she said. “If we know they are receiving … public funds, why aren’t we putting systems in place where they are accountable to the public?”

Instead, she said, “We’ve created a system where unequal outcomes are guaranteed.”

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent non-profit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Reporter Kaylee Tornay can be reached at kaylee@invw.org.

Comments

Post a Comment